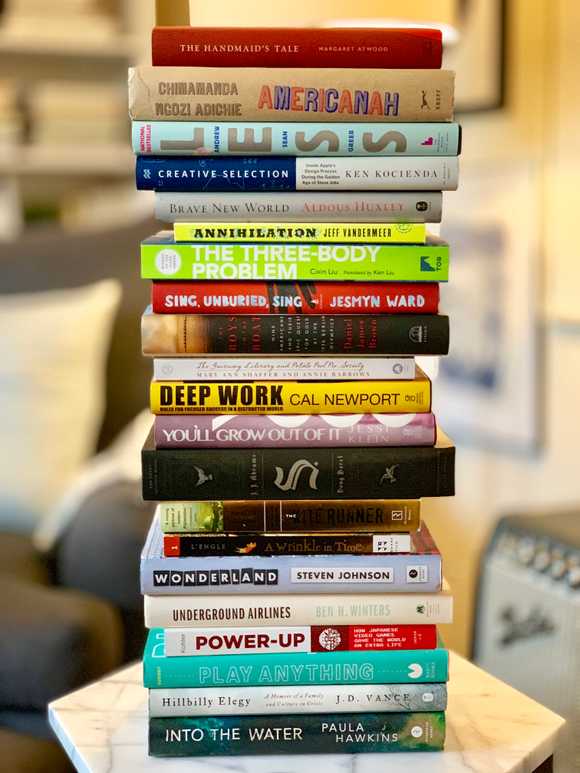

This year, I did a bit of catching up. No thanks to Nintendo and the Switch, 2017 was largely spent scavenging Hyrule and the Mushroom Kingdom. In 2018, I leapt back into books — many of which I’d been meaning to read for a few years.

Needless to say, I quite possibly read more in 2018 than any other year of my life. Honestly, I can’t say any of these reads were horrible (though I’m one to find good in anything). Some certainly better than others. All a bit scattered amongst genre.

Without further adieu, here are my 2018 reads, ordered from most favorite to least.

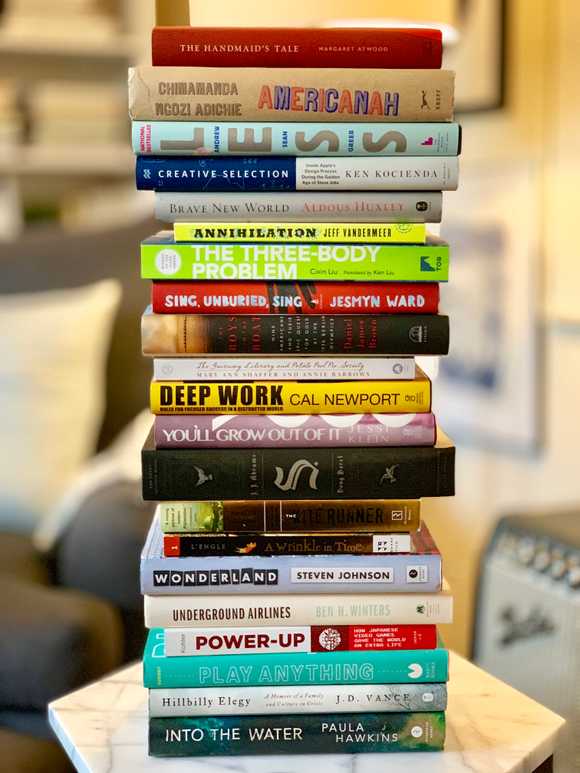

Margaret Atwood

Horribly chilling in light of the US today. The extreme justifications of Law and Government’s Will as God’s own feel too real and terrible. Published in 1985, no less.

My god, what a read.

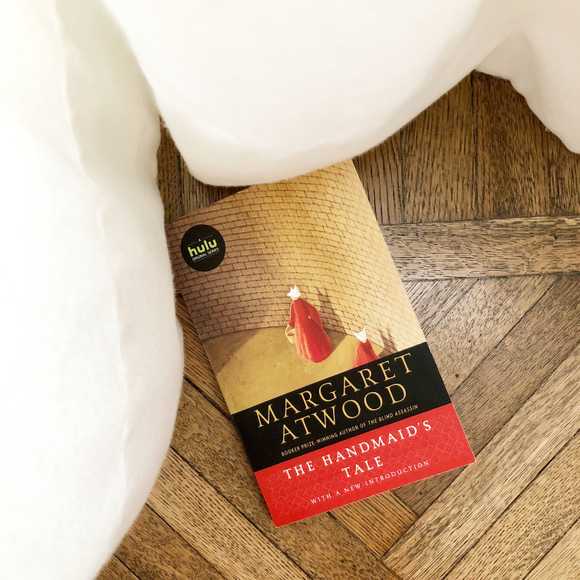

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Shortly after we moved to San Francisco, I found a copy of Americanah in our building’s shared laundry room — in the communal stack of books and magazines. I had heard great things on The New York Times Book Review Podcast and swooped it up immediately. (Truthfully, nothing stands between me and a beautifully formatted hardcover.)

A gut-wrenching love story, relatable and not. A story of America, relatable and not. A bare truth of race in this country that’s all so evident, yet can never be reinforced enough — now more than ever. A perspective unlike any other.

“Love was a kind of grief. This was what the novelists meant by suffering.”

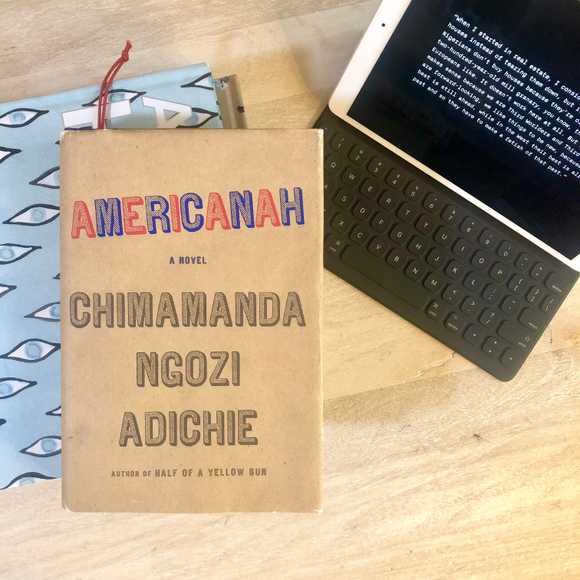

Andrew Sean Greer

What is seemingly a 2-star novel warps and wraps itself into a top-shelf, lovely comedic, and heartfelt story by a 5-star genius. So many “I’ve been there” moments and callbacks to “insignificant” details that the heartfelt and hilarious pangs resound with gut-wrenching timbre.

The story of Arthur Less is a comedic one, filled with the kind of silly anxieties, ghosts of the past, self-deprecation, self-destruction, and self-loathing we all find familiar. Best of all, a story of itself and meta and multiple levels. A protagonist no one should feel sorry for and that’s just the point.

We are all more or less Less.

Ken Kocienda

A superb look inside software development at Apple and what it means to create team culture. Hard to put down.

I came to this book by way of John Gruber’s Daring Fireball. As a manager leading a cross-functional publishing and platform development team, this is a critical peek at what makes Apple quality software.

I’m thankful to have a team staffed with creatives, designers, developers, editors, producers, and writers. Truly the intersection of technology and liberal arts. But success goes beyond the right mix of people. It takes direction and focus. I shared the seven elements Kocienda identifies with my team, asking them which element stood out most to them. Unsurprisingly, we had a healthy mix of craft, taste, inspiration, diligence, and empathy. I’ve since gone on to outfit my team with Kocienda’s book as an artifact of what it takes to get to where Apple is today and to never forget what can be accomplished with a small team.

I advise everyone to read this book.

Aldous Huxley

How did I miss this in high school? A chilling premonition of Today from 1932. Truth vs happiness. No sweet without the sour.

God in the safe and Ford on the shelves.

A masterpiece.

Jeff Vandermeer

As dreamlike, entrancing, and lush as Area X. Vibes like Sunshine, LOST, The Abyss, and Dear Esther. Extremely my jam.

The movie is way different, but just as awesome.

Cixin Liu

How do you even begin to write something this vast, imaginative, complex, and yet entertaining? Such a fun, big read. Awesome first act to a trilogy, but I’m going to need a breather before diving into book two.

Jesmyn Ward

Imaginative. Mystifying. Infuriating. Poetic. Vivid. Captures an uninhibited train of thought perfectly.

A lonesome and dooming dusk.

Daniel James Brown

Layers upon layers. Part bio, part sports rivalry, part pre-war omen. Paces like a race: quick off the line, measured through the middle, blasts-off at the end. The descriptions of the competitions had me gripped. Maybe could have been 50-100 pages shorter, but likely meant to portray the weight of perseverance.

Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows

This book came as a recommendation from my wife. She’d become insistent on me finishing so we could watch the Netflix film.

While fluffy, it’s a fascinating look at the German Occupation in the Channel Islands during WWII — a story not often told, and in the format of letters no less. An easy read full of wonderful characters and whimsy. An easy holiday read.

Cal Newport

I came to this book via The Ezra Klein Show podcast. Cal and Ezra discussed some interesting tips about maximizing productivity during large chunks of the workday. I found the idea of leaving my mornings free and scheduling meetings on the back half of my day compelling. It quickly fell apart as a manager, but the idea is beginning to help some of my employees.

For knowledge workers — engineers, academics, etc — large chunks of uninterrupted time can be critical for working deeply and making large strides in productivity, innovation, and creativity. If you can’t always be out of the shallows, find ways to minimize its impact: use a to-do list to track big items/projects; clear your inbox to remove the nagging distraction of something beckoning you; send clear correspondence with precise action items and expectations. If you have a project, find 1–4 hours to focus on it.

The one I’m working on: sign-off by 5:30 and stop thinking about work!

Jessi Klein

I’d heard about this book from (once again) The New York Times Book Review Podcast. They deemed it something like the better Amy Schumer biography.

With only a blip of a mention of Schumer, I get it. An honest, humbling, and humiliatingly hilarious look into the female experience — womanhood, comedy, writing, aging, and sexuality.

Klein shows that it’s truly impossible to empathize with everything everyone goes through. As a male, I’ll never understand the twists and turns of womanhood, no matter how many women I have in my life. On the other hand, there’s a shocking amount of humiliating and shitty situations we all share.

A light, fun, funny read that will shine a light on experiences you have had, may have, and never will have.

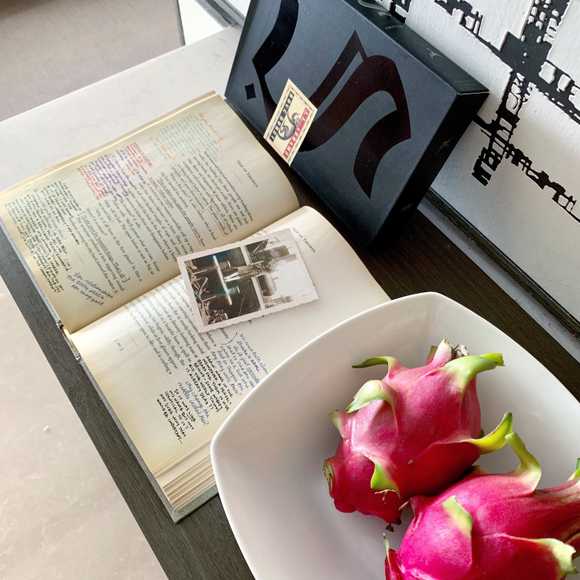

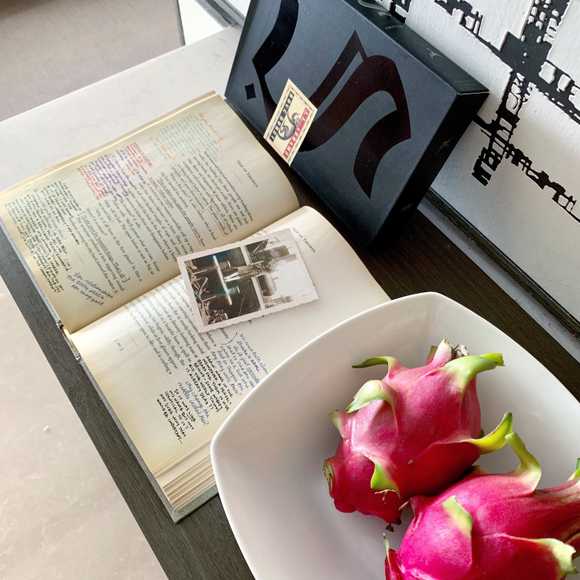

J.J. Abrams and Doug Dorst

If not entirely satisfying, a wholly original work and impressive feat. Glad to have given it a go.

I learned about this book while posting an Event at the Apple Store to the iTunes Store during my time on Apple Podcasts — an interview with J.J. Abrams and Doug Dorst. I couldn’t resist the complexity and mystery of the book. My inner-LOST nerd needed it. It only took me five years to get to it.

Khaled Hosseini

“It was only a smile, nothing more… but I’ll take it.”

A gauntlet and another solid recommendation from my sister, Megan Starr.

Madeleine L’Engle

Alice in Wonderland meets The Little Prince. A wild, snappy adventure filled with witches, aliens, and — of course — space and time travel.

Steven Johnson

I came across this book from its companion (and clever marketing vehicle) podcast Wonderland.

We are all wired with natural instincts: hunger, thirst, sex. (Hypothalamus keeping us right!) Yet, we crave and are fascinated by surprise. “When the world surprises us with something, our brains are wired to pay attention.” Even without any seemingly productive ends, we explore and yearn for new experiences. We play. “The pleasure of play is understandable. The productivity of play is harder to explain.” Play propels our creativity and innovation.

“You will find the future wherever people are having the most fun.” Humans are funny space creatures. If only we would all just play a little more.

Ben H. Winters

Gripping, thrilling, tight. Cinematic and easy to envision. A take on the reality of fending for oneself in the direst of situations. Sympathy for an antihero. Ego vs Id. Battle of conscience. Complexities unraveling themselves hours after finishing.

Chris Kohler

Great historical reference and a fun look back on video game history. Made even better by reading during a trip to Tokyo! Ended a bit misty-eyed at the Iwata remembrance. Thanks to Pavan Rajam for the recommendation.

Ian Bogost

I picked this up after reading a triple-review of Death by Video Game (ultra fav!), The Tetris Effect (fascinating), and Play Anything. I tweeted a photo of the review — proud I had read two of three books in an NYT Book Review. With permission, Mr. Bogost used the photo for his own tweet. Photo credit would have been cool, but it was still a neat moment.

Play Anything reads like an academic paper on how we define “fun”. There are plenty of choice quotes and great insights. However, they are mired in thick sets of highbrow, like diamonds in tons of rough of proof and reference. As much as Bogost preaches the ability to find fun in challenge, I couldn’t find much fun here. Bogost would call this “hardship”. At the very least, amongst bits of beautiful insight, Bogost’s writing has a musical quality. It’s easy to wade around in it, even if you’re not taking it all in.

Maybe my expectations were initially misaligned by a NYT review of books about games. I’d also argue Bogost’s title doesn’t help. Rather than “Play Anything”, this should have been titled “The Paradox of Fun”, “Fun Theory”, “The Power of Limits”, or simply “Read David Foster Wallace”.

Bogost proves to be an incredibly smart philosopher, but his philosophy of fun may be better as a longform feature rather than an entire book.

J.D. Vance

I’m a firm believer of education, but nothing benefits like a happy home. The Rust Belt is under a microscope, but these problems affect California, too.

Paula Hawkins

Fun first 2/3. Tedious final act. Illuminating epilogue. Unlikeable characters. Can’t say I’d recommend it, but suffices as a page-turner.