My daughter!

Excuse my lack of preamble, but she is without a doubt my most favorite part of 2022.

It’s very hard to describe the joy that courses through my entire mind, body, and soul every time I see her. I’ve wanted to be a father for as long as I can remember. But hours before she was due, I had this paralyzing fear that some damaged part of my brain would about-face and reject the pride of parenthood. Thankfully, I was very wrong. The second I heard her cry, my heart burst. It was one of the greatest moments of my life, and things only got better. I discovered an incredible force of nature. Instinct took over. I immediately knew exactly how to care for her; how to protect her. And not only her, but my wife who had just endured the incredibly invasive and major surgery of Caesarean section — common, yes, but it will lay out strongest person.

Caring for both my wife and daughter

For the three days we spent in the hospital, I was on constant watch for my family. The second my daughter cried for food, I was awake and ready. Every moment my wife asked for help out of bed or for a breakfast burrito, I was there. I yearned to support and care.

Prior to leaving for the hospital, I had packed my bag with books and video games, none of which I touched post-operation. I found the experience of “being there” riveting. It was the most present I’ve felt in a long time and I’ll cherish it for as long as I’m able.

Now, onto the “things”…

(Favorite) Games of the Year

- Loco Looper — A crafty iOS puzzle game built with Metal, Swift, and SwiftUI. It lulls the player into a sense of calm with very simple 6x6 railroad crafting levels, but eventually turns into an incredibly challenging puzzler, always leaving one piece to frustrate one to their wits end. Continuing the theme of my daughter, I have extremely fond memories working through Loco Looper while rocking her to sleep every 2-3 hours for weeks at a time. Hail portrait single-handed mobile games!

- Tunic — (I’m listening to the soundtrack as I write this. What a joy!) An homage to early 2D Zelda titles, printed game manuals (in foreign languages), and an unparalleled sense of discovery. I started this game on an M1 Mac and finished on Steam Deck — a joy on both. Do yourself a favor and turn on No Fail Mode. The combat doesn’t do its brilliant experience of discovery any favors.

- Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Shredder’s Revenge — I won’t go on too much here. Read my review. All I can say is that TMNT: Shredder’s Revenge is a damn near perfect brawler with wonderful nods to both the original TMNT cartoon as well as the 8- and 16-bit era of TMNT video games.

- Kirby and the Forgotten Land — I have not completed Kirby and the Forgotten Land, but that doesn’t mean it’s any less charming or impressive. For a Kirby game, I was not expecting something as rich and detailed as this. It demos poorly, so just move ahead with the purchase. You won’t regret it.

- Elden Ring? — I didn’t play many games from 2022 in 2022, but I did pick up Elden Ring last week. In the 3–4 hours I’ve played, this game is incredible. I hate the lack of explanation about the controls, menus, items, builds, etc., and I’ve avoided any enemy more difficult than two swipes of a sword, but the world, fidelity, animation, and music are jaw dropping. This is my chill game of 2022. I’m sure that will change when I actually start playing in 2023.

Mastodon

For nearly 15 years, I was a heavy Twitter user. I made connections with many people I felt I had no business connecting with, found my tribe, and boosted my blog’s reach through some fortunate retweets and endorsements. And I tweeted a lot. But the act of tweeting began to feel more like an addiction and ephemeral than something of value. It was far from the feeling I get when I write a blog post, which was becoming fewer and fewer by the year. Once Elon Musk took ownership of Twitter, I bolted. I deleted all of my tweets, more or less bid adieu to the platform, and leaned into the Mastodon account I created in 2018. And it feels fantastic.

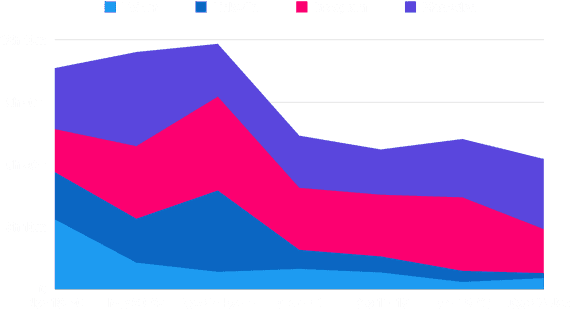

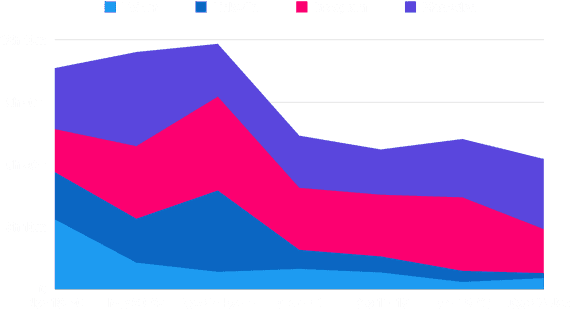

Since November 13, 2022, I’ve been monitoring my social media Screen Time:

I find these results shocking. Not only have I reduced my overall social media usage, but dropping Twitter was much easier than I thought it would be thanks to a wide adoption of Mastodon from many folks in the communities I take part in.

While my time engaging with Mastodon is on the rise, that’s not due to an algorithm. It genuinely feels like a healthier, friendlier social-network. And the decentralized nature means my content won’t just disappear.

In small part, I owe Musk thanks in prompting me to have a healthier relationship with social media. In large part, I owe Mastodon for being there when the rug of a centralized platform was pulled out from under its users. A brilliant technology at the right time.

If you’re unfamiliar with Mastodon or think it might be too complex, check out Brendon Bigley’s “How to Use Mastodon” explainer at his blog, Wavelengths.

Analogue Pocket Cores

I received my Analogue Pocket in 2021 and loved it then. But in 2022, its firmware was updated to unlock the FPGA technology inside to developers. Through this, multiple open-source “cores” have been released for the device including cores for NES, SNES, Genesis, Game Boy, Game Boy Color, and Game Boy Advance, amongst others.

These cores have changed my relationship with emulation and 8- and 16-bit retro gaming in general. Being able to hardware emulate my catalog of NES, SNES, and Genesis games and take them on the go is a childhood dream realized. In the early to mid ’90s, the best we could get was a Game Boy or Game Gear with slimmed down games, grayscale graphics, and/or poor battery life. Honestly, most of those experiences were great, but they paled in comparison Super Mario Bros. 3 on the NES, The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past on the SNES, or Sonic 2 on the Genesis. We just wanted to carry those experiences in our back pocket. And now we can. At a hardware level. The future.

Steam Deck

I’ve been missing out on PC gaming for some time. With the Steam Deck, I can finally enjoy classics like Half-Life 2, Halo, Mass Effect, etc., etc. On top of that, the ease of emulation through the Steam Deck is remarkable. While the emulation is not operating at a hardware level like the aforementioned Analogue Pocket, I am able to quickly load-up 3D favorites from PS2, PS3, GameCube, Wii, and many other consoles of yore. The Steam Deck is a wonderful companion to my Analogue Pocket, a great current-gen console (in handheld form!), and a hopeful glimpse into the future of handheld gaming.

Music

New Releases

Vinyls